I've begun a new gallery in the photography section; it's, for the moment, all stills from our past two Teachers Federation film productions for cinema and television ads. I was the on-site client representative and (perhaps more usefully) the de facto stills photographer. See the whole gallery here.

The Constant

I've just yesterday flown back to Sydney from a holiday in the States; as I left the country, the story of the attacks in Paris were unfolding and unfinished. Every news channel in the hotel displayed a barrage of information—'experts' spoke of the social situation in France, issues over immigration and inculturation, economic pressures among migrants, dissatisfaction over political reforms, involvement of the French military in North Africa, the 'War on Terror', various riots in The Republic over the past years, the history of Colonial power, religions intolerance, religious tolerance, freedom of expression, temperance of that expression, a new device that can hold any smart phone in your car's air vent, the upcoming Super Bowl, how the French government should respond, what mistakes were made by French Intelligence, the inevitable surveillance state, and so on.

Then, I flew for fourteen hours from Los Angeles to Sydney and all that fell silent. Most international flights are, for now, still free of any internet or broadcast news incursion. You've only your own reflections on current events to mull over (my 'entertainment display' was non-functional so I also did not have the selection of films to peruse either).

All these diverse and discordant voices—everyone has some opinion. Some are willing to voice them; some turn to violent action. How can I comprehend the situation of someone whose life is so different—who has a whole set of values and beliefs that are either many degrees separated or outright antithetical to mine? It takes significant dialogue (and, of course, a willingness to engage in that for both parties). But what, in the human experience of our engagement with one another, is the constant? All discussions and interactions involve variables; some of the elements can be reconciled but the equations seem to be too dynamic in the moments of conflict and confusion. What is the static constant that we all share no matter our culture, history or faith? It's silence; we are forgetting how to respect the silence of our togetherness and risk losing the only thing that we can always hold in common.

I know that the news is necessary; but I wish, for a given event, there could be an embargo for some time—that the first response, in the face of tragedy, would be silence and time to reflect. The immediate impulse to find blame, identify the early childhood traumas of the perpetrators, or trace the path of money and weapons is not, primarily, the issue at hand. These events all spring from our inability to hold a balanced space together; there is a rupture in society that tears right down through individuals because they can't find a way to hold life on common terms.

We recognise, after the fact, the necessity of silence; in memorials, in the streets, in Parliaments, there is 'a moment of silence' held by all, no matter what their political bent or religion. We need to find a way to hold silence together beforehand; we need to find these ruptured men and women in their time of injured vulnerability and learn to be silent together; to hold the quiet that leads to a discussion. What they are receiving, instead, is that onslaught of noise and rage from every quarter that drives them into further despair. If every space of mind and spirit is filled with the clamour of so many competing ideologies, there will be no room left for the common silence. What remains for the catalyst of peace? We'll face a future of desperate commentators trying to unquietly uncover why?

Guardian Australia Culture Podcast

I'm trying to bring some income (and variety) into the studio at work during idle times; this week, I recorded the Guardian Australia culture podcast. I had four journalists sitting round a table talking about the recent Melbourne festival. It was also great to observe Miles Martignoni in action; he's an experienced radio producer who calmly guided the process and then edited the material into an informative finished piece. Have a listen at this link or subscribe on iTunes here.

The dangers of Scrabble

I came across this site full of (wonderfully irreverent) animations made from a combination of Old Master paintings and whimsy.

The Mystic

I'm reading through old journals again; I wrote this in 1996 after holding a rare manuscript book from 1280. How did ancient scholars carry these words that were written and handed down so carefully over time?

He calls,

The Mystic to his Bride.

Her subtle voice returns,

Fixed into his eyes

As he in her remains.

He lifts her;

A gentle touch

Upon the ribs along her spine.

Her skin–still taught,

Though years of holding

Have formed wrinkles in her folds.

His time all spent

Beside her now.

His hands brush across her face.

He sees no age,

Yet, he stoops closer.

His eyes–grey.

In visions, he carries her,

As she does him.

His life upon her words.

And from their joining,

Two made one,

Come volumes yet unborn.

Giving in Time

My mother is in hospital at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore; she had, last Friday, major surgery to remove a rare cancerous tumour from deep within her liver. It was a very long and complex procedure that requires a surgeon of great skill and care surrounded by a hospital that can support the whole endeavour. The surgery itself went well and she is recovering now although she's having some (expected) complications and challenges. I'll write more about her journey through this in the coming weeks.

My father and I are staying on the hospital campus in a special facility provided for cancer patients and family whilst they are here for treatment. Johns Hopkins covers this vast swath of Baltmore; it's consistently rated one of the top hospitals in the United States. It was started by a Quaker man in the 1800's with an endowment that was equivalant to eleven billion dollars in today's money. I'm struck by such generosity from a man who gave what was needed in his time and now his stewardship gives back so many times more (there is a lot more to explore about Hopkins, he was an abolitionist and insisted that blacks and whites be served equally in the hospital and also set up orphanages and schools for blacks in a time when that was considered illegal). I, once again, find the subtle spirit of Quakers still resonating down through time.

I've included an image I made the other day here in the old entrance to the hospital (which is now buried in the enormity of what the campus has become). It's called Christus Consolator, though Hopkins himself was a non-sectarian and was an early advocate of multi-fatith counsel in hospitals, this was placed as an iconic symbol of guidance and comfort. I think it still stands well deep within the quiet heart of this place.

Coming by Sea to Hope and Distress

Wood that turns to stone,

That turns to bone

At the bottom of the sea;

Flotsam in the ocean,

Like the great raft

Of rubbish that is

Part of what we have

Discarded—too difficult

To address but distant enough

To ignore.

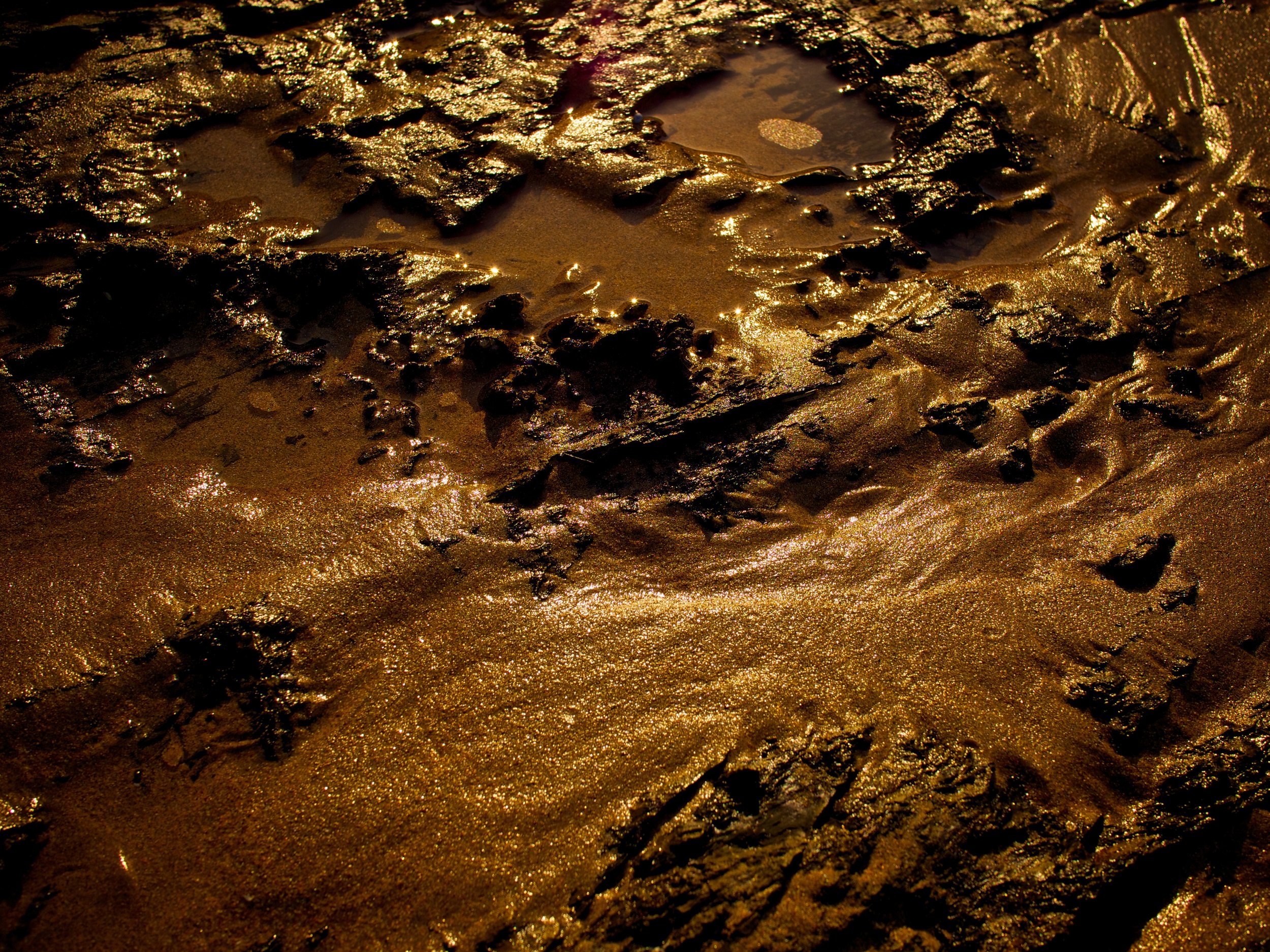

Easter by the sea

My friends, Sally and Piero, invited me down to the family holiday house near Bateman's Bay for the Easter long weekend.

Pro patria mori

Today was ANZAC Day (the Australian Memorial Day); I’m conflicted over the concept of war memorial. Earlier this week, I made this photograph of a wood carving in the mezzanine at work (click on the image to see it larger). It was commissioned in the 1950’s by the Federation to commemorate teachers who served and died in World War I & II. It depicts a prone soldier holding what seems to be either a bouquet of some sort or perhaps a handful of grasses and what I assume is meant to be a Bible in the other hand. It’s not clear whether he is resting or is, indeed, dead; the text reads ‘He served in war that we might live in peace’. That’s debatable for WWI, where the Australians suffered a terrible defeat in far away Gallipoli (observed today); perhaps less so for WWII where they were directly at risk from Japanese invasion.

I made the photograph with the thought that we would post it on the website with a bit of explanation and observance of our own; however, there was some concern that it might cause consternation and appear we were supporting war. I do not, in any form, support the idea of war. It is, by far, one of the most useless and destructive activities mankind can embark on and, especially now, the most dangerous. However, I have no problem pausing to remember the men and women who died in war. No matter how senseless the conflict may have been, people died and that is worth noting. (Though I do think that more should be done to speak of civilian deaths in wartime; those casualties, as evidenced in current conflicts, tend to get glossed over).

But then I must consider the most appropriate memorial. How do I commemorate the deaths of so many in conflicts I do not condone? There is always the risk, in ceremony, to sermonise either for or against war. I'm not sure it's appropriate to use such opportunities to criticise the situations where such sacrifices were made. I am sure thought that it's inappropriate and manipulative to use the emotion tied to such events to rally people to war or the support of a current conflict.

I wonder if, truly, the only sensible remembrance on such days is silence. What can you or I know about the situation of death in war that a particular man or woman experienced? What words of mine would add any honour to their names? I think there is much to be said, no doubt endless stories to be written and spoken of those individuals. But that is for histories and museums; on the day itself, should we not take the time to just fall silent?

There is too much risk that the words we use may colour the understanding of what war is (to either those who know—or perhaps for those experienced it and may wish to forget). Even when I was taking this picture, the methods I used could shape how the memorial is perceived. I lit it several different ways, from flat to dramatically cross-lit; depending on the position of the lights, the scene can look almost idyllic, or harsh and bleak (the one above is somewhere in-between). If something as subtle as the light across a carving can have such an effect, what might the words of sly politicians and their ilk do on a day like today when the hearts of people are so open?